The Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution clearly states, “A well regulated [sic] Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” Few other sentences in the English language have been subject to such political controversy and aggressive misinterpretation as this one. Just about every one of those twenty-seven words has been picked apart and scrutinized by legions of lawyers, lawmakers, and lobbyists across the country. What constitutes an infringement? What exactly is a “bearable arm” and who are “the people” doing the bearing? The biggest question, though, is what is meant by “well-regulated militia.” This is the contention from which many arguments from gun control arise.

As of late, some people have supported arguments against the right to keep and bear arms by suggesting that the Second Amendment protects the National Guard. Indeed, some National Guard units trace their lineage back to colonial militias and the Army National Guard as a whole claims 1636 as its year of formation. This, however, is not really the same entity to which the Second Amendment refers.

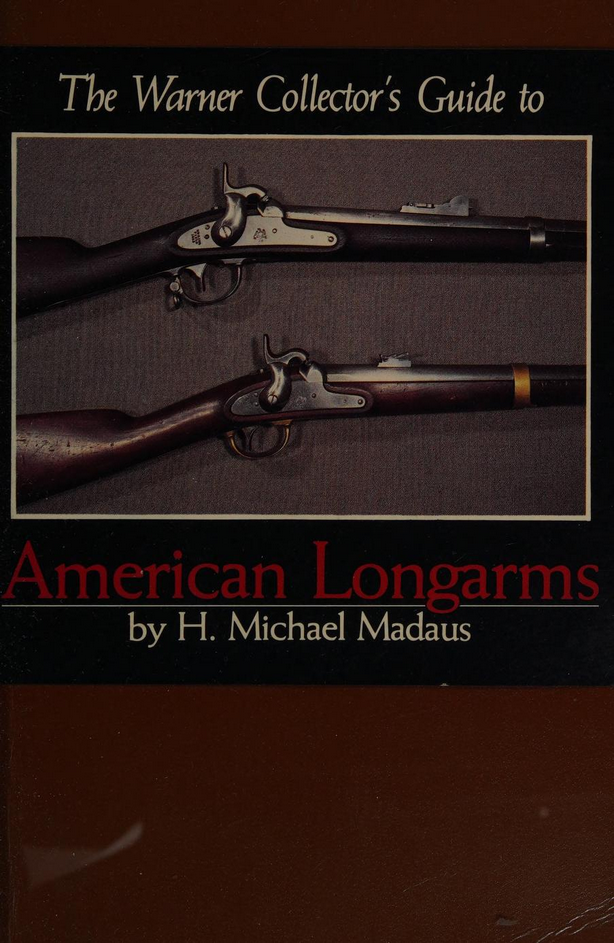

What, then, did the framers have in mind when they wrote a well-regulated militia into the Constitution? Unfortunately, we can’t go back in time and ask them personally, but we can do the next best thing: read what else they wrote on the topic. The Second U.S. Congress passed the Militia Act of 1792 in May of that year, less than five months after the Second Amendment was officially ratified. This law gives Congress the power to call up the militia, then defines what the militia actually is, in that order. It clearly states that the militia is to be composed of the body of the people—at that time, “each and every free able-bodied white male citizen of the respective States” between the ages of 18 and 45—with exceptions for postmen and some other public officials. Militia service was compulsory for those eligible, and each militiaman was required to arm himself with a musket, at least twenty-four bullets, powder, spare parts, and other equipment. The act even goes on to state that muskets should be standardized at 18 gauge, the equivalent of roughly .64 caliber.

The National Guard began to become a separate entity with the Dick Act, passed in 1903, and was formalized further with the National Defense Acts of 1916, 1920, and 1933. Today, under 10 U.S.C. §246(b), the National Guard is only one component of what should theoretically be a larger militia system. State Defense Forces are theoretically classified as the “unorganized militia,” but their limited status and capabilities conflict directly with the original intent of the Second Amendment. The militia was to be composed of the body of the people, and the regulation came in the form of minimum equipment requirements, not limitations.

As mentioned above, the original Militia Act includes lists of required equipment for each militiaman, with additional requirements for specialist troops and officers. Taken directly from the text of the law, every eligible citizen was to own:

- A good musket or firelock sufficient for balls of the eighteenth part of a pound

- A sufficient bayonet and belt

- Two spare flints

- A knapsack

- A pouch, with a box therein, to contain not less than twenty-four cartridges:

- Suited to the bore of his musket or firelock

- Each cartridge to contain a proper quantity of powder and ball

- If the militiaman had a rifle instead of a smoothbore musket:

- Shot pouch

- Powder horn

- Twenty balls suited to the bore of his rifle

- A quarter of a pound of powder

In essence, the militiaman was to have at the minimum a contemporary military-style long arm of a military caliber, a full combat load of ammunition, spare parts, a bayonet, and a set of what we now call load-bearing equipment. This would place him roughly at equipment parity with a professional infantryman of the day and allow him to train under professional soldiers.

Under the same framework, a modern militiaman would likely be required to furnish him- or herself with:

- An AR-15-type rifle chambered for 5.56×45mm and accepting standard AR-15 magazines

- A sufficient bayonet and scabbard

- A spare bolt and firing pin

- An internal-frame backpack

- A battle belt, chest rig, or plate carrier, with pouches thereon, to contain not less than six loaded 30-round magazines with one more at the ready:

- Compatible with the AR-15 platform

- Fully loaded with 5.56×45mm ammunition

On top of that, keep in mind that militiamen in the early United States received military training on the government’s dime; when the militia was activated, its members were given the same pay and benefits as Army regulars, and they were not required to serve longer than three months per year.

In summary, arguments that the Second Amendment protects the National Guard are patently false. At the time of its ratification, the National Guard would not yet exist in its current form for more than a century; the “well-regulated militia” to which the Second Amendment refers was composed of the general public, armed with privately owned military-grade equipment and trained by the government. When someone tries to make an originalist argument that the Second Amendment doesn’t give us the right to own certain weapons, counter that the Second Amendment implicitly requires us to.

Comments