Author’s Note: This blog post is adapted from a short piece I wrote for the November 2024 issue of Leatherneck, Magazine of the Marines. It is part of a series of briefs on historic long arms, commemorating the Marine Corps’ 250th anniversary year.

Technical Data

Weight: 8lb. 15oz. (1766 model, approx.)

Overall Length: 59 ¾”

Barrel Length: 44 ¾”

Chambering: .69 cal.

Feed System: muzzleloader

Operating System: flintlock

Rate of Fire: 3 rounds per minute effective

Range: 100 m effective (point target), 300 m effective (area target)

Description

During the Revolutionary War, the Kingdom of France supplied more than 100,000 muskets for the Americans to use against their mutual enemy, the British Empire. Though the Model 1763 and variants thereof were produced at St. Étienne, Maubeuge, and Charleville, the latter became an informal collective name for the French muskets.

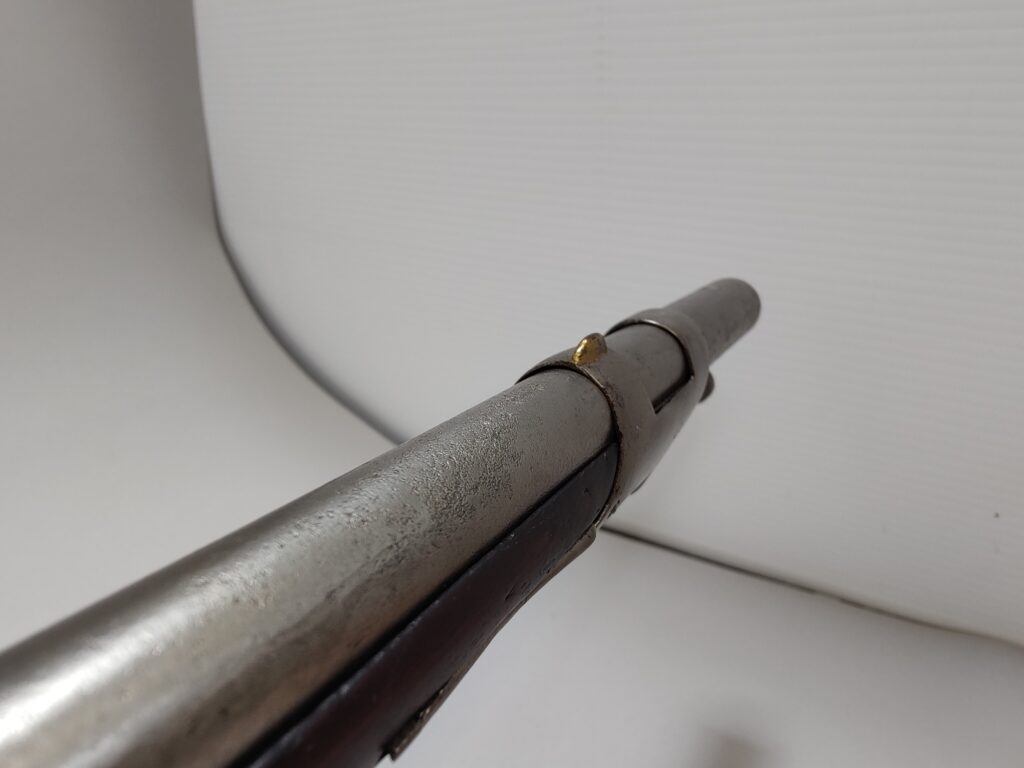

Like its contemporaries, the Charleville musket is a very simple weapon. The “lock,” or firing mechanism, achieves ignition by slamming flint against steel, hence “flint lock.” The system consists of a spring-loaded hammer with a piece of flint clamped into it, which impacts the curved steel frizzen to ignite a small amount of black powder in the flash pan. The flame then travels through a small touch hole drilled in the side of the barrel, igniting the main powder charge and firing the weapon.

Troops armed with flintlock muzzleloaders carried a typical combat load of 40 rounds and were expected to fire up to three rounds per minute. Due to the inherent inaccuracy of these smoothbore (unrifled) weapons, European armies fought in large formations, firing mass

volleys into one another at relatively close distances. To support such tactics, the rifle had a short stock and a minimal sighting system consisting only of a shotgun-style brass bead. The lock and barrel are made of unfinished steel, requiring regular cleaning and maintenance to prevent rust.

Development and Service History

At the outbreak of the American Revolution, most long arms in Continental hands were either British .75 caliber Land Pattern “Brown Bess” muskets or privately owned, craft-produced hunting arms. In 1776 and 1777, the nascent U.S. government began to purchase surplus French muskets in large numbers; throughout the war, Continental soldiers and Marines fielded more Charlevilles than any other type.

The Charleville was an adequately modern weapon for its day. Compared to the Land Pattern, it is slightly lighter, and its smaller caliber meant the musket balls were about 22 percent lighter as well. Because they were built by hand, these weapons did not use interchangeable parts: if a component broke or wore out, a trained gunsmith would have had to fabricate a replacement from scratch and tolerance it to fit that individual weapon.

Although the Charleville remained in service until about 1812, it was officially replaced by the domestically produced Model 1795 musket, which first made its way into the hands of Marines around 1803. Built at the Springfield Arsenal (no relation to the modern-day company of the same name), the Model 1795 was a clone of the improved Model 1768 Charleville.